Quick and Quiet: Supersonic Flight Promises To Hush the Sonic Boom

Resembling a futuristic paper airplane, this aircraft holds the secret to quiet supersonic commercial travel over land. The X-plane aims to turn the sonic boom associated with supersonic flight into more of a sonic heartbeat.

The Bell X-1, piloted by U.S. Air Force Capt. Chuck Yeager, reached 700 mph on Oct. 14, 1947. At Mach 1.06, it was the first airplane to fly faster than the speed of sound. But at speeds greater than Mach 1, air pressure disturbances around airplanes merge to form shock waves that create sonic booms, heard and felt 30 miles away.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Americans filed some 40,000 claims against the Air Force, whose supersonic jets were making a ruckus over land. Then in 1973, the FAA banned overland supersonic commercial flights because of sonic booms—a prohibition that remains in effect today.

NASA and a team led by Lockheed Martin are making advances that bring the goal of quiet supersonic commercial travel over land closer to reality. On Feb. 29, NASA announced it had awarded a $20 million contract to Lockheed’s team to design a low-sonic-boom X-plane that would support efforts to replace the current prohibition with a new standard that would allow acceptable en-route supersonic noise.

The job of the Lockheed team over the next 17 months will be to come up with baseline requirements, specifications and a preliminary design for a demonstration aircraft.

Michael Buonanno, chief engineer for NASA’s Quiet Supersonic Technology (QueSST) X-plane program, said the foundation was laid from 2010 to 2013 with the N+2 Supersonic Validations Program.

“We worked with NASA to develop the necessary design tools and experimental techniques to accurately shape the vehicle so that its sonic-boom signature will be perceived as a sonic heartbeat sound rather than the typical loud double-bang that today’s supersonic aircraft produce,” Buonanno said.

The QueSST jet would fly at speeds of Mach 1.4, about 1,100 mph, twice the speed of today’s commercial airliners and nearly as fast as the Concorde. Buonanno said boom-reduction shaping tools have been validated by analysis, wind-tunnel testing and flight experiments.

Designing for Low-Impact Sound

The N+2 Supersonic concept, pictured above, laid the foundation for NASA’s Quiet Supersonic Technology (QueSST) X-plane program.

The X-plane’s promise hinges on its streamlined design, resembling the paper airplanes we let sail in our youth. Its futuristic look includes a long, slender fuselage, a highly swept delta wing and multiple control surfaces to tailor the distribution of pressure and lift around the vehicle.

“In order to have low sonic boom, you need to specifically design to have it,” Buonanno said. “It’s a nuanced and detail-oriented task to set up the shape of the vehicle so that the shock waves that result from supersonic flight don’t coalesce and result in that loud double-bang.”

In the airline industry’s current tube-and-wings model, shock waves largely roll off and then meld into a sonic boom. The aerodynamic X-plane, however, is designed to scatter multiple shock waves and minimize their cumulative effect, producing only a rumble or soft thump.

“You try to minimize the strength of the shock, so you have a very sharp nose on the aircraft, but you have to extend it a long way past the fuselage,” said Thomas Corke, professor of engineering at the University of Notre Dame.

Corke, director of Notre Dame’s Institute for Flow Physics and Control, conducted hypersonic Mach 6 experiments at the Air Force Academy in Colorado—at a speed more than four times faster than the X-plane’s.

“The idea is that there is no way to avoid a shock wave supersonically,” Corke said. “The [X-plane] design doesn’t eliminate shock, it just minimizes it, so what’s perceived on the ground is almost imperceptible.”

Lockheed will support the NASA led team to gauge community response to the sonic boom thump. NASA’s intention is to fly the QueSST aircraft demonstrator over communities across the country and collect data from civilians on noise acceptability levels, Buonanno said.

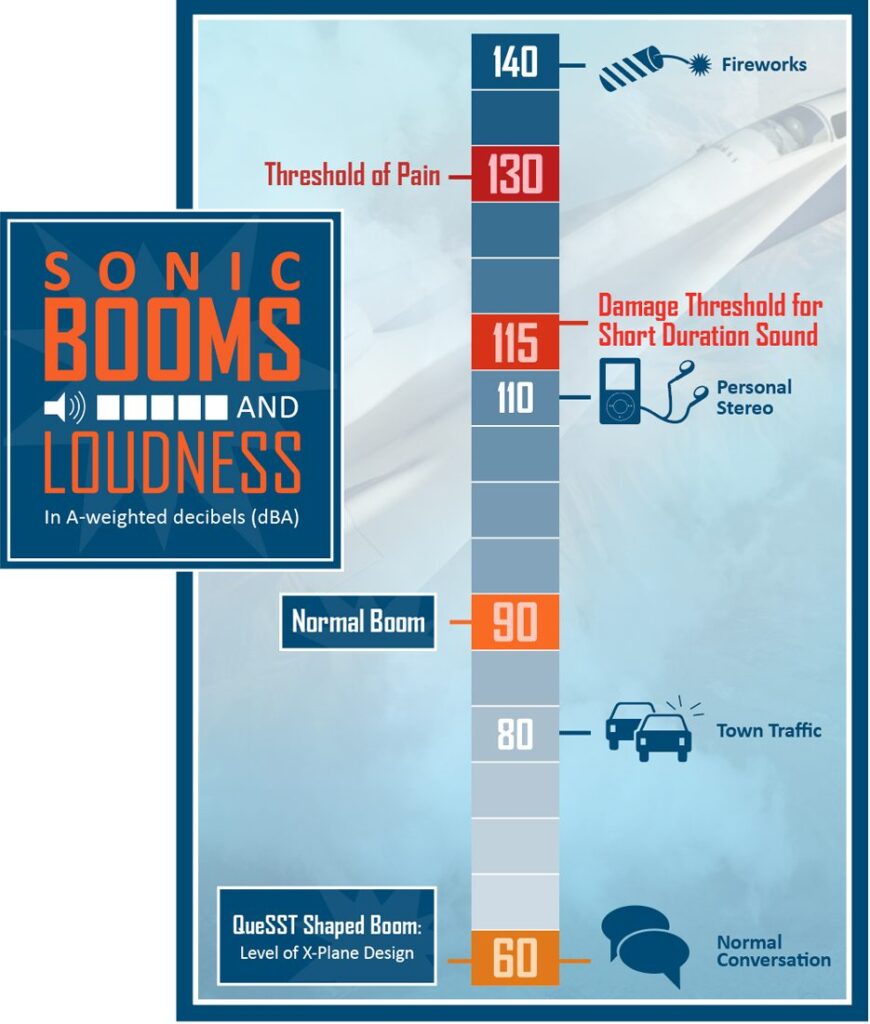

The demonstrator, at 90 feet long, will be smaller than future civil supersonic aircraft. The goal is to eventually have commercial supersonic transportation. The Concorde’s sound at cruising altitude was about 90 A-weighted decibels, but Buonanno said that based on tests, the X-plane would generate about 60 A-weighted decibels of noise. Quick and quiet are the buzz words.

Buonanno and Corke are buoyed by advances that may help overturn the 43-year ban on overland supersonic flight, a goal spelled out by NASA, Buonanno said.

“NASA stated this is a mission for themselves,” Buonanno said. “They think they need to lead the efforts to change the regulations.”

Corke said it’s fitting that NASA, in partnership with Lockheed Martin’s team, is the one moving forward with this compelling X-plane model. The government agency better known for facilitating outer space exploration for nearly 60 years has long sought quick, quiet travel closer to Earth.

“It was originally developed at NASA—first in the early 1990s,” Corke said. “So it’s been in development for a long time.”

So, Just How Loud is a Sonic Boom?