Tel Aviv University professor Karen Avraham and MD-PhD student Shahar Taiber. Photo courtesy of Tel Aviv University.

Israel’s TAU Team Develops New Gene Therapy For Deafness

JERUSALEM (JNS/Israel21c) – Delivering healthy genetic material into the inner ear cells of mice with a genetic defect that causes deafness enables the cells to function normally, according to a new study from Tel Aviv University (TAU).

The novel treatment prevented the gradual deterioration of hearing in these mice, and could potentially lead to a breakthrough in treating children born with various mutations that eventually cause deafness.

The study, led by professor Karen Avraham of the Department of Human Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry at TAU’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Sagol School of Neuroscience, was published in EMBO Molecular Medicine on Dec. 22.

Deafness is the most common sensory disability worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, about half a billion people have hearing loss, and this figure is expected to double in the coming decades. One in every 200 children is born with a hearing impairment, and one in every 1,000 is born deaf. In about half of these cases, deafness is caused by a genetic mutation. A hundred different genes are associated with hereditary deafness.

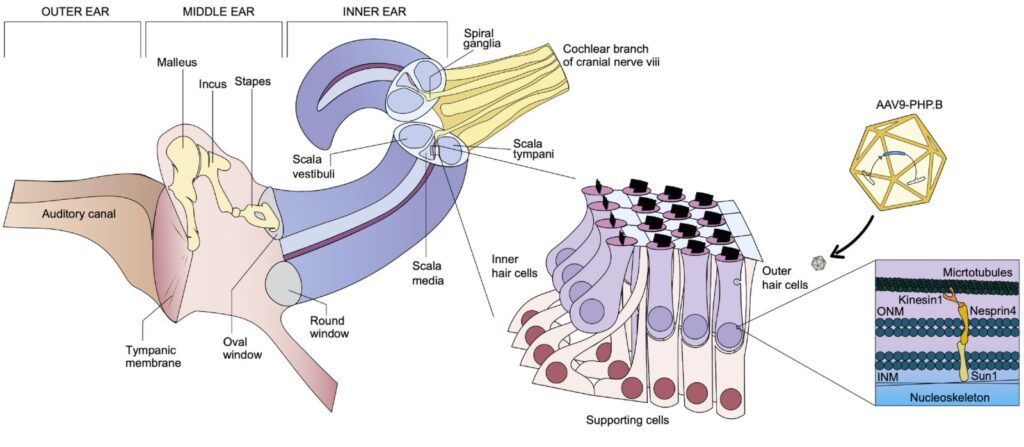

Schematic representation of inner ear anatomy. Image courtesy of EMBO Molecular Medicine.

“In this study we focused on genetic deafness caused by a mutation in the SYNE4 gene—a rare deafness discovered by our lab several years ago in two Israeli families, and since then identified in Turkey and the U.K. as well,” said Avraham.

“Children inheriting the defective gene from both parents are born with normal hearing, but they gradually lose their hearing during childhood. The mutation causes mislocation of cell nuclei in the hair cells inside the cochlea of the inner ear, which serve as sound wave receptors and are essential for hearing. This defect leads to the degeneration and eventual death of hair cells.”

Special delivery

Avraham’s lab used an innovative gene therapy technology: They created a harmless synthetic virus that served as a delivery vehicle for a normal version of the gene that is defective in both the mouse model and the affected human families.

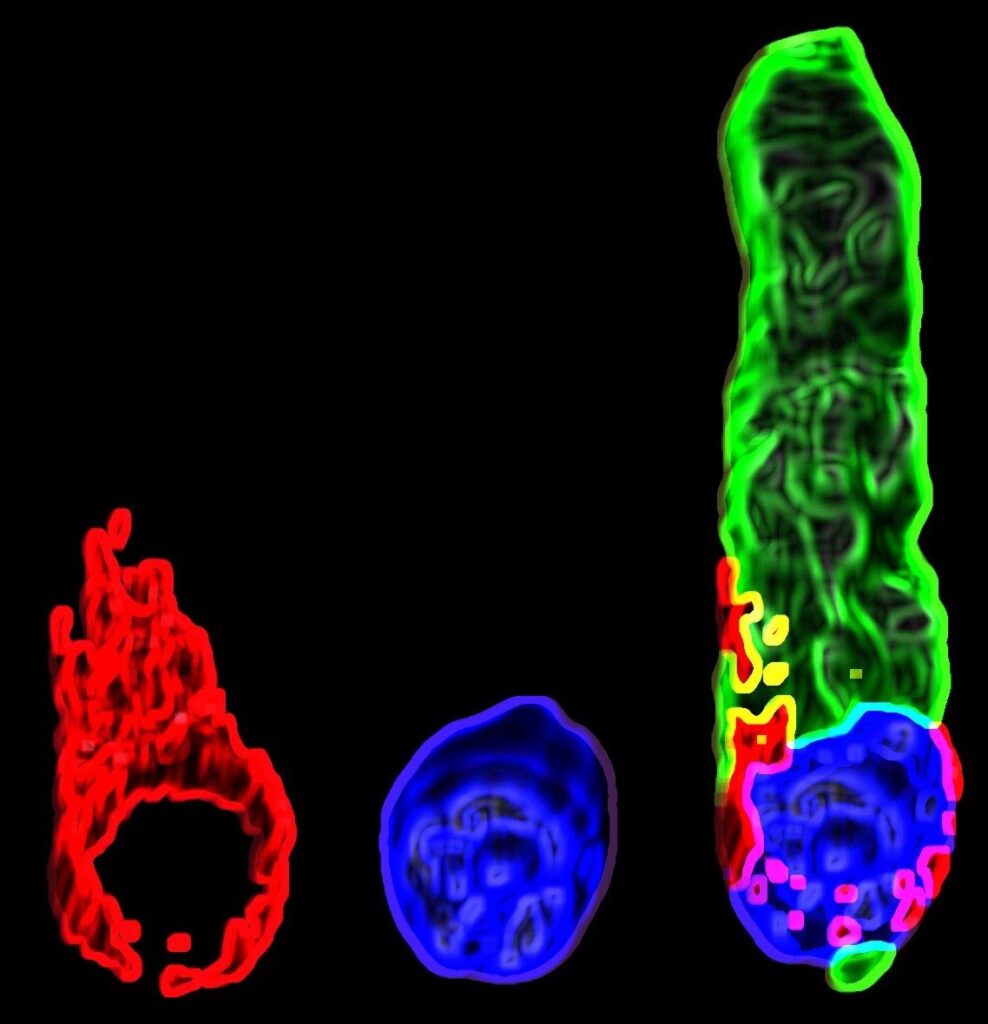

3D rendering of a hair cell of a treated mouse: The nucleus is stained in blue, the cytoskeleton in green and Nesprin 4 (an outer nuclear membrane protein) is stained in red. Photo by Shahar Taiber.

Shahar Taiber, one of Avraham’s students on the combined MD-PhD track, said, “We injected the virus into the inner ear of the mice, so that it entered the hair cells and released its genetic payload. By so doing, we repaired the defect in the hair cells and enabled them to mature and function normally.”

The treatment was administered soon after birth and the mice’s hearing was then monitored using both physiological and behavioral tests.

“The findings are most promising,” said professor Jeffrey Holt from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, a collaborator on the study. “Treated mice developed normal hearing, with sensitivity almost identical to that of healthy mice who do not have the mutation.”

The scientists are now developing similar therapies for other mutations that cause deafness.

“This is an important study that shows that inner-ear gene therapy can be effectively applied to a mouse model of SYNE4 deafness to rescue hearing,” said Dr. Wade Chien from the U.S. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders’ Inner Ear Gene Therapy Program and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Chien was not involved in the study.

“The magnitude of hearing recovery is impressive,” he said. “This study is a part of a growing body of literature showing that gene therapy can be successfully applied to mouse models of hereditary hearing loss, and it illustrates the enormous potential of gene therapy as a treatment for deafness.”

Additional contributors included professor David Sprinzak from the School of Neurobiology, Biochemistry and Biophysics at TAU’s George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences. The study was supported by the U.S.-Israel Binational Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Research Council and the Israel Precision Medicine Partnership Program of the Israel Science Foundation.